Illicit financial flows punch holes in the public purse across the African continent. Over the past five decades Africa has lost in excess of US$ 1 trillion in illicit financial flows. This amount dwarfed Africa’s receipts of overseas development assistance during this period and also exceeded foreign direct investment into Africa.

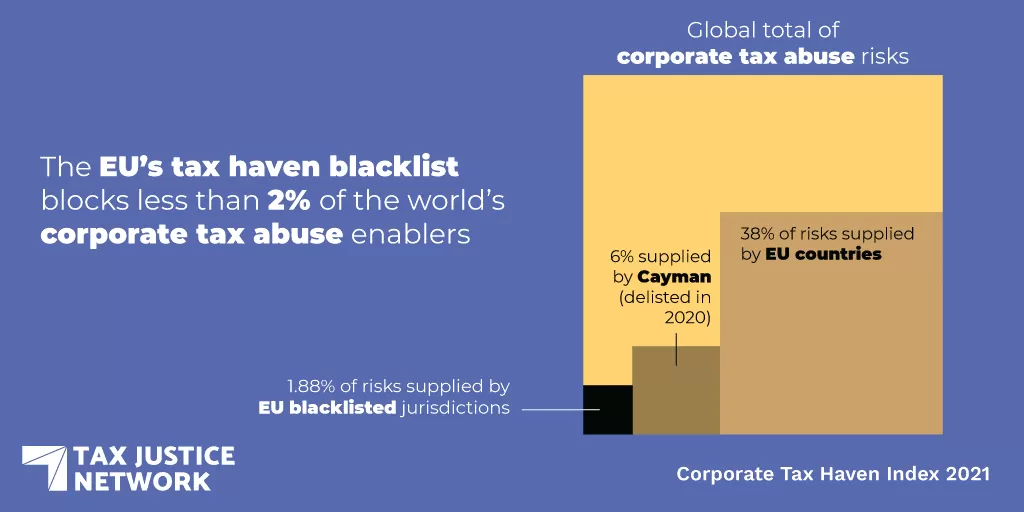

Two-thirds of corporate tax abuse, which forms a substantial part of illicit financial flows, is enabled by member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which is the leading rule-maker on international tax. This was revealed in the biennial Corporate Tax Haven Index 2021 published by the Tax Justice Network. The index exposes how this club of rich countries has created a system that allows multinational companies to pay less taxes in the countries where they should with direct effects on developing countries’ tax revenues.

According to Lyla Latif, Managing Director of the University of Nairobi’s Journal on Financing for Development and Director of the African Centre for Tax and Governance, “African countries inherited a tax system put in place by some of the old powers assembled today as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)”. She explains that: “This system, which is at play today, based its entire tax philosophy around mobilisation of taxable income, regardless of where it was sourced from resident countries. This, by design, embedded inequality within the international tax regime in which African states have become vulnerable and open to the scramble for tax. Such vulnerability expressed in the form of base erosion and profit shifting, is largely responsible for the removal of the provision of social services and welfare from the centre of the post-colonial African government’s fiscal obligation to its taxpayers.” Transforming the current international tax system will go a long way to ensuring African governments can protect the rights of citizens and fill half of the financing gap to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

Rich countries responsible for the bulk of corporate tax abuse

A club of rich countries setting global rules on corporate tax are responsible for over two-thirds of global tax abuse. That tax abuse costs the world eight times the European Union’s Coronavirus Global Response Fund and three times the combined health budget of African countries

Among the biggest enablers of global corporate tax abuse are four British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies (#1 British Virgin Islands, #2 Cayman Islands, #3 Bermuda, and #8 Jersey). The islands are followed closely by the Netherlands (#4), Switzerland (#5) and Luxembourg (#6). These countries claim to be developing equitable global tax rules, yet are responsible for the lion’s share of illicit financial flows.

Britain seeks through its Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office to “reduce poverty and tackle global challenges”. Yet the UK and its spider web of Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories are collectively responsible for 31 percent of the world’s corporate tax abuse risks. US$ 160 billion of public money is lost every year as a result. In these Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories, the UK has full powers to implement or veto law-making and the British Crown has the power to appoint key government officials.

The Netherlands enables 5.5 per cent of global corporate tax risks, yet the Dutch government also claims it wants to “reduce poverty and social inequality [… and] prevent conflicts and instability”. Switzerland states that in its “development cooperation with the South” it is “fighting poverty and ensuring no one is left behind” and Luxembourg claims in its “ethos of sustainable development […that] man, woman and child tak[e] centre stage”, while they respectively enable 5.1 and 4.1 per cent of global corporate tax risks.

The UN High Level Panel on International Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity (FACTI) makes clear in its recently launched report, that illicit financial flows “worsen inequalities, fuel instability, undermine governance, and damage public trust. Ultimately, they contribute to States not being able to fulfil their human rights obligations.”

These European countries and their dependencies are therefore key in the design and propping up of a system that is an antithesis to development. As Léonce Ndikumana, Distinguished Professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, writes in the Black Lives Shattered edition of the Tax Justice Focus, donor countries “could increase the effectiveness of their aid to the continent by helping to plug the leakage of Africa’s wealth by denying a home to illicit flows from the continent”.

Africa and the Corporate Tax Haven Index

The Corporate Tax Haven Index shows once again that most African countries pose a minimal risk to other countries in terms of enabling profiting shifting by multinational companies. Nine countries are assessed Botswana, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Mauritius, Seychelles, South Africa and Tanzania.

Based on meticulous research of national laws, policies and practice, each of the 70 countries included in the Corporate Tax Haven Index are given a score. Unlike the European Union’s blacklist which only assesses and includes non-EU countries and their tax policies, the index assesses how much a country’s tax system enables corporate tax abuse and then combines that score with the amount of corporate activity taking place in the country in order to determine how much corporate activity is being put at risk of tax abuse. To measure how much of the financial activity conducted by multinational corporations around the world is hosted by the jurisdiction, the International Monetary Fund’s data on foreign direct investment is used. The greater the share of the world’s corporate activity jeopardised by the country’s tax system, the higher the country ranks on the index.

Countries on the European Union’s tax haven blacklist enable 2 per cent of global corporate tax abuse. The Netherlands, Switzerland & Luxembourg enable 15 per cent but are exempt by default.

Mauritius continues to play a corrosive role in Africa with its “authorised company regime”, raft of tax exemptions and almost non-existent transparency requirements for corporate reporting. The State of Tax Justice 2020 reports that each year Mauritius costs other countries at least US$ 961 million in lost tax by enabling cross-border corporate tax abuse. Mauritius also costs other countries $432 million in lost tax by enabling private tax evasion, bring the total of tax countries lose due to Mauritius to $1,392 million every year.

- Corporate Tax Haven Index Ranking: 15

- Financial Secrecy Index Ranking: 51

- Tax Loss Each Year To Tax Havens: $ 170.121.791

- Tax Loss Inflicted On Other Countries: $ 1.392.976.160

Other countries on the continent have taken steps to protect themselves and also contribute less to corporate tax havenry. Kenya, for example, abolished the exemption on withholding tax for dividends paid by special economic zone enterprises, developers or operators to non-residents. It also increased the withholding tax rate for dividends paid to a non-resident person from 10 to 15 per cent. This will help Kenya counter corporate tax avoidance strategies and protect its own tax base. For example, subsidiaries of multinationals operating may reduce their taxable income and therefore corporate income taxes paid by deducting payments made to other companies in other countries within the same corporate group. Therefore, withholding taxes on any payments, such as dividends in Kenya’s case, have the potential to compensate for losses. Kenya could improve its tax collection further if it were to limit deductions on other payments subsidiaries make – royalties, interest and service payments.

In 2020, Botswana abolished the Botswana Investment and Trade Centre company regime, which operated in similar ways to patent box regimes found in other jurisdictions. Patent box regimes provide preferential tax treatment for intellectual property rights and thus enable cross-border profit shifting into these tax regimes, undermining the tax bases of jurisdictions elsewhere. This important change made by Botswana therefore protects the tax base of other countries, and the Seychelles should now follow in abolishing patent box regimes in their jurisdiction. Mauritius also abolished its patent box regime, although unfortunately it continues to exempt foreign royalties from the tax base. The Seychelles has also abolished the special licence regime for companies.

As Tax Justice Network and Tax Justice Network Africa have found in the past, African countries contribute much less to the problem of tax abuse than European Union and OECD member states and their dependencies. Yet transparency and anti-avoidance measures are still less robust than in OECD countries. There is a need for policy improvements in African countries to curb and protect against corporate tax abuse.

Improving corporate filing requirements is a low cost step for African administrations to improve transparency to tackle base erosion and profit shifting. Unfortunately none of the nine African countries assessed in the Corporate Tax Haven Index require all companies to keep accounting records, to file accounts annually with a government agency, and for a government agency to publish these online at low or no cost.

To identify profit shifting risks, such as through transfer mispricing, African tax authorities should oblige multinational companies to provide information on where they carry out their activities, where they declare their profits and where they pay their taxes. This means that a step African countries must take is to oblige multinationals headquartered within their jurisdictions to publish public country by country reports and subsidiaries of foreign multinationals to file country by country reports locally.

A positive development is that the disclosure of payments to government at the mining project level has already started on a voluntary basis in the extractives sector for African countries participating in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. This shows what is possible. Ghana and Liberia have made progress on contract disclosure in the extractives sector, and while it is no panacea, contract transparency should improve government enforcement and incentivise fair contracts.

The Panama Papers and subsequent leaks have revealed the role of intermediaries, such as tax advisors in tax planning schemes. As a result, governments across the world have been spurred on to require taxpayers and tax advisors to report tax abuse schemes that are being used or marketed and promoted. Of the African countries examined by the Corporate Tax Haven Index, only South Africa has implemented this rule. Other African countries could follow suit. Mandatory reporting requirements also act as a deterrent against using tax abuse schemes and flag areas of uncertainty in the tax law that need clarifying or improving. These domestic actions and others supported by the Tax Justice Network Africa, Tax Justice Network and partners will go some way to Stop The Bleeding, in the words of a campaign Tax Justice Network Africa spearheads. Yet fundamental change will come only by reprogramming the international system of tax rules

Other countries on the continent have taken steps to protect themselves and also contribute less to corporate tax havenry. Kenya, for example, abolished the exemption on withholding tax for dividends paid by special economic zone enterprises, developers or operators to non-residents. It also increased the withholding tax rate for dividends paid to a non-resident person from 10 to 15 per cent. This will help Kenya counter corporate tax avoidance strategies and protect its own tax base. For example, subsidiaries of multinationals operating may reduce their taxable income and therefore corporate income taxes paid by deducting payments made to other companies in other countries within the same corporate group. Therefore, withholding taxes on any payments, such as dividends in Kenya’s case, have the potential to compensate for losses. Kenya could improve its tax collection further if it were to limit deductions on other payments subsidiaries make – royalties, interest and service payments.

In 2020, Botswana abolished the Botswana Investment and Trade Centre company regime, which operated in similar ways to patent box regimes found in other jurisdictions. Patent box regimes provide preferential tax treatment for intellectual property rights and thus enable cross-border profit shifting into these tax regimes, undermining the tax bases of jurisdictions elsewhere. This important change made by Botswana therefore protects the tax base of other countries, and the Seychelles should now follow in abolishing patent box regimes in their jurisdiction. Mauritius also abolished its patent box regime, although unfortunately it continues to exempt foreign royalties from the tax base. The Seychelles has also abolished the special licence regime for companies.

As Tax Justice Network and Tax Justice Network Africa have found in the past, African countries contribute much less to the problem of tax abuse than European Union and OECD member states and their dependencies. Yet transparency and anti-avoidance measures are still less robust than in OECD countries. There is a need for policy improvements in African countries to curb and protect against corporate tax abuse.

Improving corporate filing requirements is a low cost step for African administrations to improve transparency to tackle base erosion and profit shifting. Unfortunately none of the nine African countries assessed in the Corporate Tax Haven Index require all companies to keep accounting records, to file accounts annually with a government agency, and for a government agency to publish these online at low or no cost.

To identify profit shifting risks, such as through transfer mispricing, African tax authorities should oblige multinational companies to provide information on where they carry out their activities, where they declare their profits and where they pay their taxes. This means that a step African countries must take is to oblige multinationals headquartered within their jurisdictions to publish public country by country reports and subsidiaries of foreign multinationals to file country by country reports locally.

A positive development is that the disclosure of payments to government at the mining project level has already started on a voluntary basis in the extractives sector for African countries participating in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. This shows what is possible. Ghana and Liberia have made progress on contract disclosure in the extractives sector, and while it is no panacea, contract transparency should improve government enforcement and incentivise fair contracts.

The Panama Papers and subsequent leaks have revealed the role of intermediaries, such as tax advisors in tax planning schemes. As a result, governments across the world have been spurred on to require taxpayers and tax advisors to report tax abuse schemes that are being used or marketed and promoted. Of the African countries examined by the Corporate Tax Haven Index, only South Africa has implemented this rule. Other African countries could follow suit. Mandatory reporting requirements also act as a deterrent against using tax abuse schemes and flag areas of uncertainty in the tax law that need clarifying or improving. These domestic actions and others supported by the Tax Justice Network Africa, Tax Justice Network and partners will go some way to Stop The Bleeding, in the words of a campaign Tax Justice Network Africa spearheads. Yet fundamental change will come only by reprogramming the international system of tax rules.

Collective action is needed by African countries and others to shift the power from the club of rich countries at the OECD to the United Nations, reinforcing their work with a UN Tax Convention. Only then will we get closer to international tax rules that are designed in a genuinely representative way, reflecting the needs of all countries, and not just those in the exclusive OECD club.